Everyone in London turned up to see the stone in the kirkyard with the sword sticking out of it. Like, everyone. And everyone tried to pull the sword out and failed.

The lines got so long that the kirk’s priest finally had to put up a sign: “Only the True King of Briton may pull this sword from this stone.”

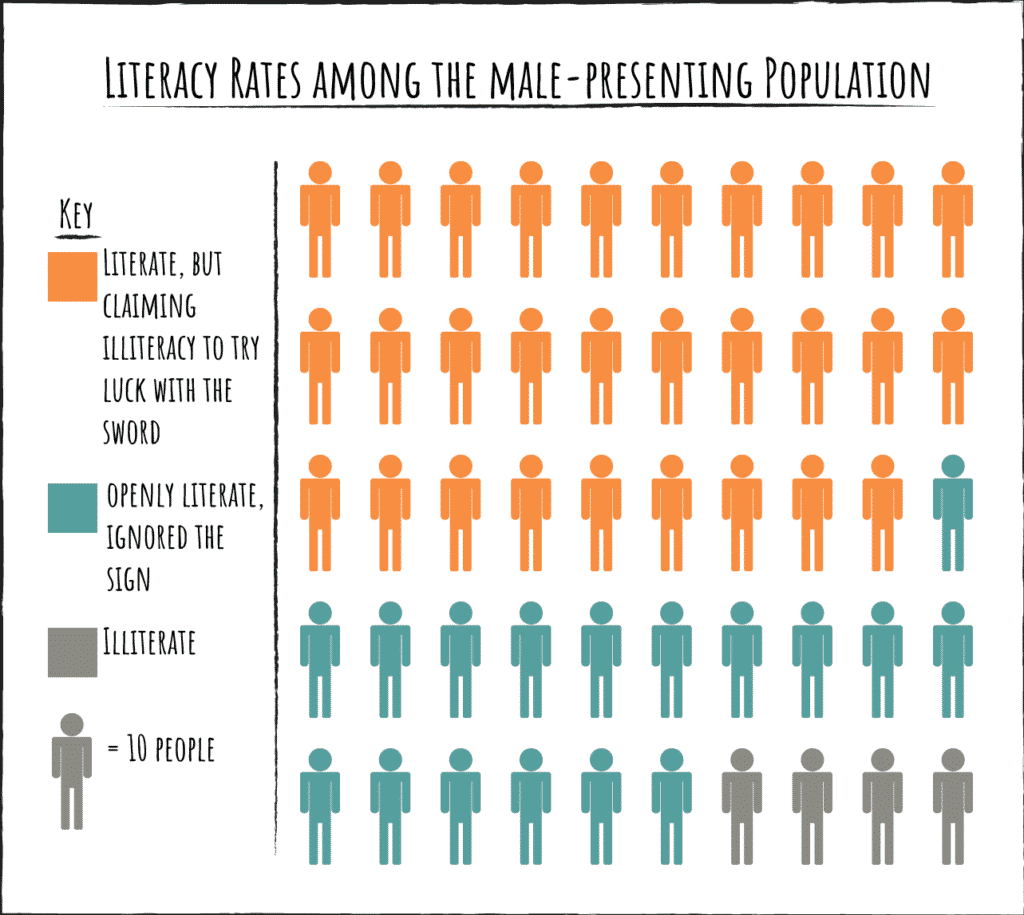

You and I both know that no one heeded this. Sure, literacy rates had improved during Uther and Igraine’s reign, but suddenly a shitton of people found themselves unable to read a simple sign. And those that did bother to pay attention missed the part where only the True King could wield it—they wanted to try their luck in the vain wish that maybe they were adopted or something.

As the Winter Solstice tournament drew closer, London became more and more crowded. Combatants poured in from all over the kingdom, followed by their entourages and spectators.

And you know that all these new people had to try their strength with the sword in the stone. Pretty soon, it became A Thing To Do for all the young knights on a night out: try their luck with the sword, then head out to the tavern to try their luck with some wenches, and cap off their debauched evening with top banter over some cheeky eel pies. A right proper evening, as they said back in those days.

It got to the point where the kirk priest had to call in crowd control. He sent up visiting hours (terce to vespers) and requested a donation for one try at the sword. (The donation did come with the forgiveness sin—naturally, the larger the sum, the more sins were forgiven, thought the majority were lustful thoughts and regretting eating too many pies.)

The priest didn’t need to worry too much, for the fervor over the tournament soon eclipsed the sword in popularity. In that the final week, the priest had only one visitor come to see the mysterious sword: Morgan le Fay.Morgan wasn’t interested in taking the throne for herself (ruling would interfere with her reading schedule), but the stone had magic properties that piqued her curiosity and warranted deep study.

To say that the year wasn’t going well for Sir Ector and his sons would be an understatement.

First, early that spring, one of his mills caught on fire. Sir Ector, Sir Kay, and Arthur joined the town in rebuilding it so it would be ready to make flour by the harvest. It meant that they missed the summons to court when Uther was dying.

Then, one of the lower fields flooded. It was thankfully one that had been set aside to fallow, but Ector and the boys were out digging a new drain when the Uther’s death announcement arrived. The new drain put their farmers behind in their yearly maintenance, so Ector, Kay, and Arthur spent September and October pitching in and repairing roofs before the cold set in.

That time, they did receive the invitation to join the tournament. However: “We can’t go,” Ector said.

“But, Father, I have to go,” Kay said. “This is my one chance to prove how good I am at fighting.”

To say that he threw himself upon a divan in despair at Ector’s decision would be inaccurate. First, divans were very rare in the kingdom, and such a luxury was beyond the means of a simple country knight. Second, Kay was far too old and too noble to clutch his chest and wail in agony. He simply settled onto a chair and thought about how wrong his father was to ignore a royal invitation; and if his bottom lip stuck out a bit, well, that was just how he thought.

But Ector was older, wiser, and just as stubborn. “There’s too much to do here. The smithy’s roof still needs to be rethatched, and the kennels need—”

Kay sat up at this. “We’ll fix every roof in the village before we go. We won’t sleep until we do.”

“‘We?’”

“Me and Arthur. We can do it.”

Arthur, who was fetching gloves for his brother and had just returned to the great hall, asked, “What are we doing?”

“Fixing things. Don’t question me.” Kay scowled. “Really, what kind of squire questions his knight?”

“I suppose,” Ector said, musing aloud, “as long as the kennels are decent by All Soul’s Day, we can go.”

The boys gave such a cheer to this (even though Arthur still did not yet know why they cheered) that they missed the part about the stone in the London kirkyard. Kay, eager to keep his word, immediately got started. He and Arthur worked whenever and wherever they had light. In less than a fortnight, they had Ector’s keep and the surrounding village in better shape than ever.

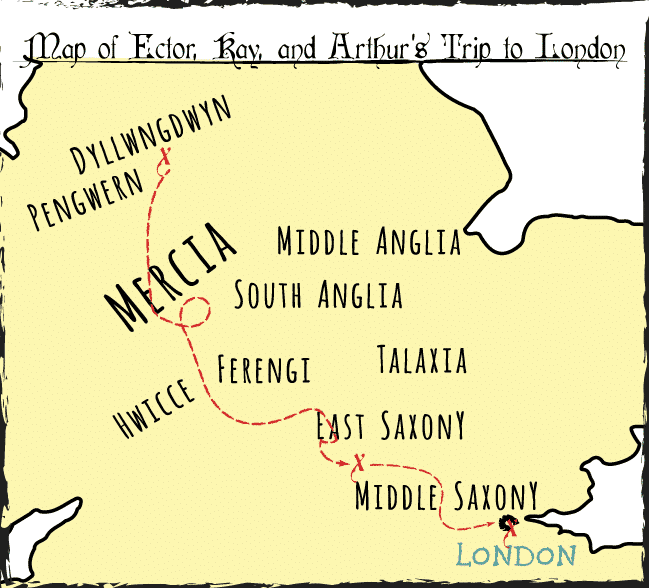

Ector reluctantly kept his end of the bargain. Three days after All Soul’s Day, he, Kay, and Arthur loaded up a wagon, polished their saddles, and headed out to London. The journey should have taken about nine days.

It took them a month and a half.

First, Ector’s horse threw a shoe. They were in the middle of the woods, so Kay and Arthur had to go find the nearest blacksmith, which lost them two days. They got lost somewhere between Mercia and Ferengi, which cost them a week entirely. And, just as they crossed into Middle Saxony, Arthur fell ill and they were waylaid at an inn for the better part of December.

Finally, two days before the Winter Solstice Tournament was set to begin, Ector, Kay, and Arthur arrived in London.